Drinking fountain on the county courthouse lawn,

Halifax, North Carolina, 1938

Topics on the Page

The Niagara Movement and the History of the NAACP

Plessy V. Ferguson

African Americans and Baseball

The Harlem Renaissance

Poetry and Poets of the Harlem Renaissance

Men of the Civil Rights Movement

- W.E.B. DuBois

- Marcus Garvey and the UNIA

- Booker T. Washington

- Lewis Latimer

Women of the Civil Rights Movement

Cross-Links

Cross-Links

Segregated Billiard Hall, Memphis Tennessee, 1939

Focus Question: How did African Americans struggle to gain basic civil rights in post-Civil War America?

Click here for a timeline of African American history

W. E. B. Du Bois's American Negro Exhibit for the 1900 Paris Exposition

W. E. B. Du Bois's American Negro Exhibit for the 1900 Paris Exposition

In 1920, Blacks owned 14 percent of the nation's farms; today less than 1 percent of all farms.

The Top Ten African American Inventors from Scholastic, including Elijah McCoy, Lewis Latimer, Granville T. Woods, and Madam C. J. Walker.

The Top Ten African American Inventors from Scholastic, including Elijah McCoy, Lewis Latimer, Granville T. Woods, and Madam C. J. Walker.

The Niagara Movement and the History of NAACP

Cross-Link: The Niagara Movement and the History of the NAACP

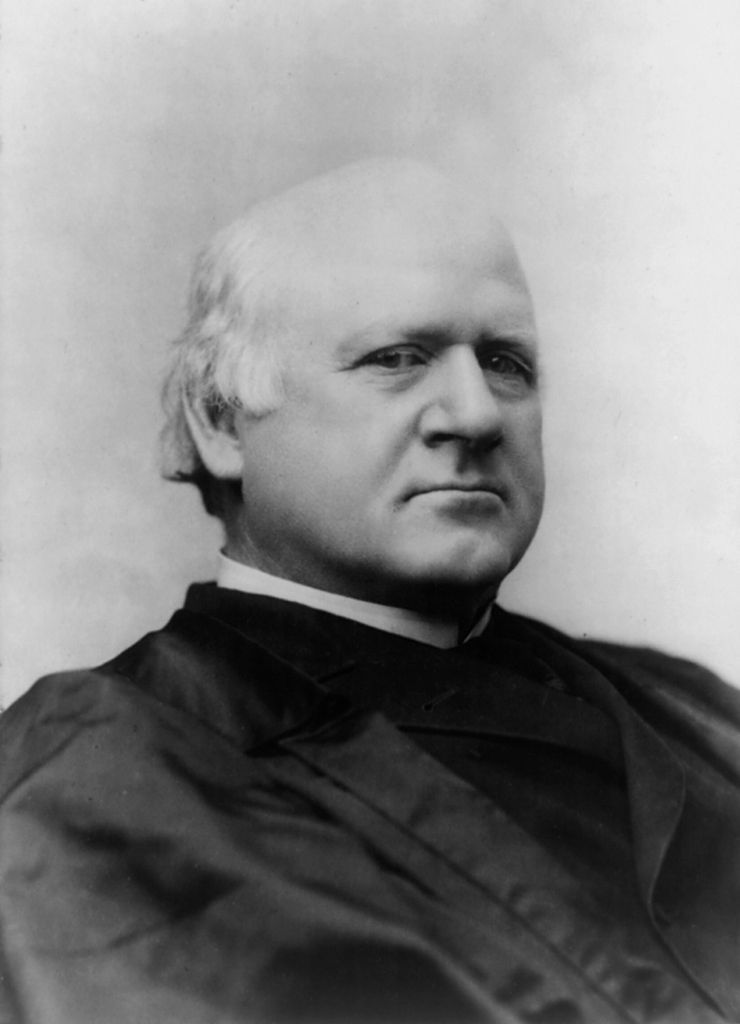

The first president of the NAACP was Moorfield Storey, a White lawyer from Boston, Massachusetts.

Anne Moody was a Mississippi native who joined the NAACP in the post-Civil War era, along with other pro-rights organizations. She detailed her experiences in her memoir, Coming of Age in Mississippi.

Anne Moody was a Mississippi native who joined the NAACP in the post-Civil War era, along with other pro-rights organizations. She detailed her experiences in her memoir, Coming of Age in Mississippi.

Plessy V. Ferguson Supreme Court Case (1896)

Plessy V. Ferguson Supreme Court Case (1896)

Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan

Homer Plessy, a light-skinned African American, was arrested for sitting in the "white" car of a train. His lawyer argued that the separate train cars violated the 13th and 14th Amendments.

The Supreme Court ruled by a 7 to 1 vote that the doctrine of separate but equal was constitutional, establishing a standard that prevailed for more than 50 years until the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

The lone dissenter was Justice John Marshall Harlan from Kentucky.

- Click here for more information.

For a complete text of the Supreme Court's decision, visit this page.

Learning plan "Keeping Them Apart: Plessy v. Ferguson and the Black Experience in Post-Reconstruction America"

Learning plan "Keeping Them Apart: Plessy v. Ferguson and the Black Experience in Post-Reconstruction America"

African Americans and Baseball

|

| Homestead Grays at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, 1913 |

In the 20 years after the Civil War, about 200 African American baseball teams formed. They mostly played each other, since only a few areas allowed interracial playing.

In 1890, the National Association of Baseball Players forbade African Americans from playing. This formally banned black teams from the organized leagues for 50 years. However, the African American teams kept playing. They continued to play each other and occasionally faced white teams.

In 1920, Rube Foster (owner of Chicago American Giants) created an all black league: The Negro National League. This league consisted of Midwestern teams. The North and South regions also created their own leagues. These leagues were successful but fell apart during the Clutch Plague.

After the Depression, the National League formed to replace the African American regional teams. The first African American player to be signed to a Major League team was Jackie Robinson in 1946, who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Slowly, other Major League teams signed African American players and National League disbanded. The last of the National League's African American teams broke up in 1960. Click here for more information from PBS

For information on African American baseball, go the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Ken Burns has a documentary, "Baseball: the Tenth Inning" that features information on African American baseball players. Click here for the PBS companion site.

Click Here to see the integration Timeline by MLB.com

|

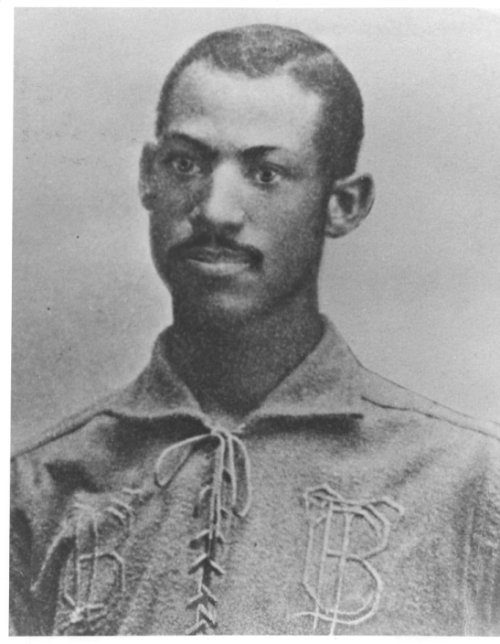

| Moses Fleetwood Walker |

For a short quiz, go to Baseball in Black and White

Moses Fleetwood Walker was the first African American to play in the major leagues of professional baseball until Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947.

Click here for an ESPN article from April 19, 2013, on why African Americans are participating less in professional baseball.

Click here to watch a short youtube video on the decline of African Americans in baseball

The Harlem Renaissance

Between the end of World War 1 and the beginning of the Great Depression, Black America went through a rich cutlural and artistic renaissance which began in Harlem, NYC. From this movement, a pride in Black life and culture gained traction and was exemplified in contemporary art and movements against segregation and discrimination.

Poetry and Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance

-I, Too by Langston Hughes

-If We Must Die by Claude McKay

-November Cotton Flower by Jean Toomer

-America by Claude McKay

-Brass Spitoons by Langston Hughes

-The Lynching by Claude McKay

These poems show the emerging focus on discrimination and the notion of fighting for freedom overseas when that freedom did not exist for Black Americans. They are all from prominent Black poets coming out of the Harlem Renaissance (posted by Willa MacLennan, April 2023).

W.E.B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was a famous scholar, editor, and African American activist and was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The NAACP is the largest, and oldest, civil rights organization in America. Du Bois set his life to fighting discrimination and racism, making significant contributions to racial, political, and historical aspects of the United States in the first half of the 20thcentury.

Du Bois served as editor of The Crisis magazine and also published several scholarly works on race and African American history.

Link here for the current The Crisis website

- W.E.B. Du Bois was born in 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. There were around 25, no more than 50 however, black people in a population of about the 5,000 people of Great Barrington. Du Bois’ mother was a domestic worker and his father was a barber who died when Du Bois was very young. At the age of 15, he became the local correspondent for the New York Globe. In this position, Du Bois dedicated his duty to pushing his race, black, forward by the means of lectures and editorials that reflected on the need of blacks to make themselves politicized.

- Du Bois’ mother died in 1884 when he was but 16 years old, but he worked on as a timekeeper at a local mill and became the first African American to graduate from the school that he was attending. Du Bois graduated from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, and received his Ph. D. from Harvard University. Upon doing so, he became a pioneer in the civil rights movement.

- Living in Nashville gave him a new experience about African American culture. He also played witness to the effects if racism with which people treat others who have a different skin color than them. It was during this time period that Du Bois’ ideas were shaped his beliefs and ideas about race relations. These ideas would last him his entire lifetime.

- On the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, February 12, 1909, 60 black and white citizens, including Du Bois, formed the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Du Bois became a member of the NAACP board and edited a journal of opinions called The Crisis.

- Du Bois played an important role in the ongoing development of the NAACP. In 1945 he represented the association in San Francisco, California, during the establishment of the United Nations.

- In 1899, Daniel A.P. Murray, an African American researcher and historian at the Library of Congress, worked with Du Bois and others to put together pictures and other items to show the state of African Americans as the 20th century began.

- In 1900, their award-winning “Negro Exhibition” debuted in Paris, France. In the exhibit, Du Bois showed that African Americans, in the 35 years since the Civil War, had come to an amazing distance since being an enslaved people. This exhibition showed that African Americans were and essential and productive part of American society. However, Du Bois and others were aware that stronger measures needed to be installed for the grasping of the full rights of his people.

The UMass Libraries have a wonderful digital collection of Du Bois' Papers. They are linked HERE

His role as a pioneering Pan-Africanist was memorialized by the few who understood the genius of the man and neglected by the many who were afraid that his loquacious espousals would unite the oppressed throughout the world into revolution.

Du Bois coined the term "Talented Tenth," referring to his plan to create an elite leadership class of African-Africans that constituted the ten percent most intelligent members of the African-American population. The speech in which he sets forth this idea can be found here.

- By the time of his death in 1963, Du Bois wrote 17 books, edited four journals and played a key role in reshaping black-white relations in America. Click here for the website Digital Du Bois from the Du Bois Library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

- Click here for a selection of Du Bois writings by decade.

Marcus Garvey

Marcus Garvey was born in St. Ann’s Bay, Saint Ann Parish, Jamaica, on the seventeenth of August, 1887. His father was Marcus Mosiah Garvey, who was a mason, and his mother was Sarah Jane Richards, who was a domestic worker and farmer. Garvey had eleven siblings. Of this eleven, only Garvey and his sister, Indiana, reached maturity. His father was known to have a large library. Garvey gained his love for reading and interest in books from his father.

He was a published, journalist, entrepreneur, and the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL). Garvey created a “Back to Africa” movement in the Unites states and became an inspirational figure for later civil rights activists. This movement eventually inspired other movements including the Nation of Islam and the Rastafari movement, which proclaims Garvey as a prophet. Garvey said that he wanted those of African ancestry to “redeem” Africa. He also wanted the European Colonial powers to leave it.

At the age of 14, Garvey left school and became the apprentice of a printer where he led a strike for higher wages. From 1910 to 1912, he traveled in South and Central America, also visiting London. Upon his return to Jamaica in 1914, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and upon his move to Harlem, New York in 1916, UNIA strived. By this time, Garvey was a formidable speaker and spoke publicly across America.

In 1922, Garvey was arrested for mail fraud in connection with the sale of the stock of the Black Star Line, which was a means of transport of African Americans back to West Africa and was part of his Back to Africa movement. The Black Star Line had failed by then. He was sent to prison and was deported to Jamaica. In 1935, he moved to London permanently. He died on June 10, 1940. In 1964, his body was returned to Jamaica, where he was declared the country’s first national hero.

The UNIA had a huge impact on the African Diaspora in the Early 20th century and the ideals introduced in it maintain today. These ideals and objectives, seen in full here, were one of the movements that led to Black Nationalism and the Black Power Movement. The idea that all Black people who can cite their lineage back to Africa (but specifically those persons who were displaced from Africa by the atrocities) can and should come together with a distinctive culture and cultural pride is the very general definition of Black Power and Pride that was spurred by the UNIA.

Click here for primary sources on Garvey, including editorials, memos, and speeches.

Click here for a lesson plan on Garvey and Nationalism

Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington, 1905

Booker T. Washington was a lecturer, a civil rights and human rights activist, and an educational administrator as well as a professor and an organization founder and author and poet.

Booker T. Washington was born in Hale’s Ford, Virginia on the Burroughs tobacco farm in 1856. His mother was a black slave who worked as a cook and his father was a white man who had owned a small farm. The laws of the time made Booker a slave also. Booker went to school in Franklin Count as a book carrier for one of James Burroughs’ daughters.

After emancipation Booker’s family was poverty-stricken, forcing Booker to work in salt furnaces and coal mines at the age of 9. He took a job that started at 4:00a.m. so that he could go to school later in the day. His parents had no money to helm him, so he had to walk 200 miles to attend the Hampton Institute in Virginia and had to pay his own tuition and boarding fee by working as a janitor.

Booker thought that an education would raise his people to equality in the United States. He became a teacher, teaching in his hometown and then at the Hampton Institute. In 1881, Booker founded the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, become recognized as the nation’s top and foremost black educator. As the head of the institute, Booker traveled the country raising funds from blacks and whites alike. In a short time, he became a well-known speaker. In 1895, Booker was asked to speak at the opening of the Cotton States Exposition which was an unprecedented honor for a black person.

.png) His Atlanta Compromise speech explained that black could secure their constitutional rights through the betterment of themselves morally and economically, not through the change in legal and political elements. Although his stand angered some blacks, whites approved of his views and thus major achievement was to win over diverse elements among southern whites. Without those people, the programs that Booker had envisioned would not have been actualized.

His Atlanta Compromise speech explained that black could secure their constitutional rights through the betterment of themselves morally and economically, not through the change in legal and political elements. Although his stand angered some blacks, whites approved of his views and thus major achievement was to win over diverse elements among southern whites. Without those people, the programs that Booker had envisioned would not have been actualized.

.png) Press play to listen to the Cast Down Your Bucket Where You Are Atlanta Compromise speech (1895) with the only surviving record of his voice

Press play to listen to the Cast Down Your Bucket Where You Are Atlanta Compromise speech (1895) with the only surviving record of his voice

|

| Andrew Carnegie and Robert Ogden visiting Tuskegee in 1906 |

Booker’s social philosophy was that work was the key to success. "There was no period of my life that was devoted to play," he once wrote, "From the time that I can remember anything, almost every day of my life has been occupied in some kind of labor."

Booker helped to establish the National Negro Business League, as well as instituting a variety of programs for rural extension work.

Later in his life, Booker moved away from his accommodationist policies. He spoke out with new honesty and attacked racism. In 1915, he joined the ranks with former critics to protest the stereotypical portrayal of blacks in the movie, “Birth of a Nation.” Some months later, Booker died at the age of 59. Booker T. Washington is best remembered for helping blacks rise up from economic slavery that held them down long after they were free citizens.

Click here for a lesson plan on Booker T. Washington vs W.E.B. Du Bois

Click here for online resources on Booker T. Washington.

Click here for a timeline on Washington

Click here for the audiobook Up From Slavery.

George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver was born into slavery in 1864.

He was kidnapped along with his sister and mother from the Carver farm when he was only a few weeks old. They were sold at auction in Kentucky, but a Carver family friend found George and returned him to the Carver farm.

After the Civil War, the Carver family adopted and educated George and his brother. After graduating from high school, he was accepted into Highland College in Kansas. The college rescinded his acceptance when they learned he was black. He ended up attending Iowa State Agricultural College, where he was the first black student. He received a bachelor and masters degree in botany. After graduation, he was hired by Booker T. Washington to teach at Tuskegee.

At Tuskegee, he did research on crop rotation and alternative cash crops. These methods helped the struggling African American sharecroppers.

Carver also did a lot of research on peanuts, soybeans, sweet potatoes, and pecans. Carver also researched plastics, paints, dyes, and a special kind of gasoline. He proposed that Congress create a tariff on imported peanuts, which they did. Carver spent a lot of time raising awareness for agriculture, racial equality, and the achievements of Tuskegee.

Click here for a full biography on Carver

Click here for an interactive exhibition from the Field Museum on George Washington Carver and his many achievements.

Click here for a timeline of George Washington Carver's life from the state Historical Society of Missouri.

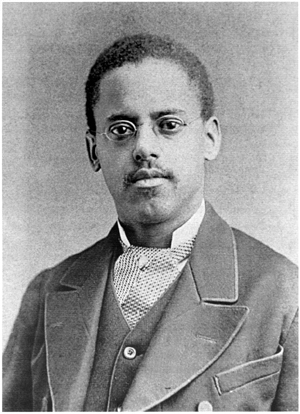

Lewis Latimer helped develop the first commercially viable electric light.

Lewis Howard Latimer, 1882

He was the only African American member of Thomas Edison's team of inventors.

He was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts.

For a discussion of Lewis Latimer's efforts to represent African Americans as equal members of society, see Inventing a Better Life: Latimer's Technical Career, 1888-1928 from Rutgers University (Blueprint for Change: The Life and Times of Lewis H. Latimer).

Sources

- Sayen, Melissa (2007). Carrie Chapman Catt: A Biography. Retrieved April 25, 2007, from Carrie Chapman Catt Web site: http://www.catt.org/ccabout.html

- The Library of Congress, (1998). Carrie Chapman Catt. Retrieved April 25, 2007, from National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection Web site: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/naw/cattbio.html

- Hynes, Gerald C. (2007). A Biographical Sketch of W.E.B. DuBois. Retrieved April 25, 2007, from W.E.B. DuBois Learning Center Web site: http://www.duboislc.org/html/DuBoisBio.html

- Liberty of Congress, (2007). W.E.B. Du Bois. Retrieved April 25, 2007, from America's story from America's library Web site: http://www.americaslibrary.gov/cgi-bin/page.cgi/aa/dubois

- Corp, Toonari (2007). Black American History. Retrieved April 25, 2007, from Africanaonline.com Web site: http://www.africanaonline.com/orga_naacp.htm

- NAAPC National Headquaters, (2006). History. Retrieved April 25, 2007, from NAACP Web site: http://www.naacp.org/about/history/index.htm

- Thomson Gale, (2007). Black history: Booker Taliafero Washington. Retrieved April 25, 2007, from Thomson Gale Web site: http://www.gale.com/free_resources/bhm/bio/washington_b.htm

- National Park Service. U.S Department of the interior, (2006). Up from slavery. Retrieved April 25, 2007, from Booker T Washinton National Monument Home Page Web site: http://www.nps.gov/archive/bowa/btwbio.html

- British Broadasting Corporation, (2007). Historic figure: Marcus Garvey. Retrieved April 26, 2007, from bbc Web site: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/garvey_marcus.shtml

- Board of Trustees, (2006). Alice Paul. Retrieved April 26, 2007, from Like Wood Public Library Web site: http://www.lkwdpl.org/wihohio/paul-ali.htm

- National women's hall of fame, (2007). Women of the hall: Alice Paul. Retrieved April 26, 2007, from National women's hall of fame Web site: http://www.greatwomen.org/women.php?action=viewone&id=118

- Prominent African American Women, (2018), from https://historyplex.com/african-american-women-in-civil-rights-movement

African American Women in Civil Rights Movement

Rosa Parks

Rosa Parks Biography https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v8A9gvb5Fh0

'Mother of the Modern-Day Civil Rights Movement', Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 - October 24, 2005) was an African-American civil rights activist

On December 1, 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, Parks broke this law - she refused to obey the order and was arrested.

Her act of defiance became a national symbol and many more followed her by not giving up their seats.

This event led to Montgomery Bus Boycott, igniting the Civil Rights movement.

She later, helped Martin Luther King launch the national Civil Rights Movement.

Jo Ann Robinson

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (1912 - 1992) was a civil rights activist and educator in Montgomery, Alabama, who helped Rosa Parks fight for the racial justice in 1955.

in 1949, she herself had been a victim of racial abuse when she was verbally accused by a bus driver

In 1955, when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man and was arrested, Robinson, with permission from Parks, mimeographed 35,000 handbills and called for a boycott of Montgomery buses

The boycott continued for a year and Montgomery Improvement Association was established.

Martin Luther king became the president of the association and Robinson served its executive board.

Ella Barker

Ella Josephine Baker (December 13, 1903 - December 13, 1986) was one of the first African-American civil and human rights activists in 1930s.

She mentored young civil rights leaders such as Rosa Parks, Diane Nash, Bob Mosses

She worked for about 5 decades but, we do not know much about her, because she was a behind-the-scenes activist

Had it not been the efforts of these African-American women, Martin Luther King would never had made the achievements he has and blacks would not have gained the racial justice.

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.